Search Results

130 results found with an empty search

- NEW INSIGHTS ON CLIMATE RESILIENT SHELTERS PRESENTED AT THE FOREIGN CORRESPONDENTS’ CLUB IN BANGKOK

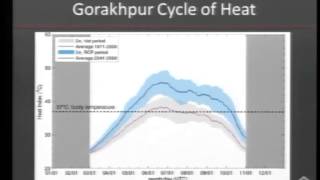

Improving the design of shelter—the homes, apartments and buildings where people live—can build the resilience of individuals and families in South and Southeast Asia to climate related disasters, according to new research from the Institute for Social and Environmental Transition–International (ISET) recently presented at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club in Bangkok, Thailand. ISET’s work was funded by the Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN) and looked at the impacts climate change will have on natural disasters in Asia, with a specific focus on typhoons in Vietnam, flooding in India, and temperature increases and heat waves in Pakistan. Shelter is a critically important element in any city or community. Homes are often the single largest asset owned by a family or individual, and damaged and lost shelters account for the highest monetary loss in climate related disasters[1]. For most low-income households, their homes are also where income-generating activities occur creating a greater dependence on structures. When destroyed, families and individuals have a reduced ability to bounce back quickly and recover from not only their structural and asset losses, but their inability to work. The peri-urban populations around rapidly growing cities are often exposed to disasters due to the locations where these communities settle. In order to understand how to build shelters that would withstand and protect families during and after disasters, ISET conducted design competitions in Da Nang, Vietnam and Gorakhpur, India where teams of local architecture students submitted ideas for resilient homes. The competition helped spark conversations about the needs of residents and introduced future architects and designers to the questions and concerns of resilience. Resilient Shelter Cost and Benefits Climate-based cost benefit analyses were conducted to understand the value of new shelter designs. Across the three countries, investments in improved shelter showed high benefit to cost ratios for individuals and households under a range of future scenarios. These findings were bolstered by experience on the ground, 250 homes incorporating resilient designs were built in Da Nang under a loan program supported by The Rockefeller Foundation. Last year, the homes that have been built under this program survived Typhoon Nari, even when nearby houses were damaged or destroyed. As a result, demand for these homes has been increasing. Despite the value of new resilient designs, the research also identified an area where changes in shelters may not be able to have as large of an impact—temperature increases. Throughout the world, temperature is expected to increase over the coming decades. Notably, many regions will see that the minimum temperatures experienced on a given day may increase more than maximum temperatures. People across Asia may find that they are increasingly exposed to temperatures above 37 degrees Celsius, the temperature of the human body and a critical threshold related to health and well being, and that during the hot season both daytime and nighttime temperatures may remain above this point. These kinds of temperature patterns could have dramatic effects, particularly on women, the elderly, children and other vulnerable populations that are often confined to homes and indoor spaces and therefore have little access to outside cooling. Apart from air conditioning, which is prohibitively expensive for many, there are few measures that can truly reduce temperatures, and those that are available are not effective when minimum temperatures increase for extended periods of time. Bangkok Dissemination Event At the presentation of this research in Bangkok, scholars and leaders from top development organizations and research institutions, including US Agency for International Development, The Rockefeller Foundation, Oxford University, The Asia Disaster Preparedness Center and King Mongkut’s Institute for Technology at Lat Krabang, among others, discussed the implications of this research and how the findings can be applied. Attendees expressed interest in understanding how to scale up the findings from the resilient design competitions and the cost benefit analyses. Much of the discussion at the event focused on the various levels from which this problem could be addressed. At an individual scale, homeowners and builders need to be educated and empowered to make changes to their homes. In cities like Gorakhpur, wealthier and more educated citizens are already making investments in homes with resilient designs; the key is to ensure that other citizens have the knowledge and ability to do the same. Training and education programs for contractors and builders were highlighted as a pathway for sharing knowledge and building these skills. At a more macroscopic level, policy and regulation change could promote shifts in shelter design and construction. For instance, standardizing and updating building codes to integrate elements of resilient design could spur incorporation across a region. At the same time a range of, city, provincial, and national policies need to be modified and linked so that governments at all levels are working towards improved shelter. As part of this research, some of this is already happening. New training materials that build on the experience in Gorakhpur were developed by the National Department for Disaster Management in New Delhi and will be shared with regional and provincial governments across India. Shelter Challenges One of the largest challenges for upgrading shelter, though, lies in the cost. In particular, new and improved homes and other buildings require a significant investment up front. Most families and individuals do not have the kind of resources to make this investment on their own. Loan programs, like the kind developed in Da Nang, are one potential solution, but they require families or individuals to take on a high level of risk. The question of how to make sustainable and accessible ‘forward financing’ available is one that has been raised across many sectors, including disaster risk reduction. Developing solutions that allow for sufficient financing up front to incent changes, while at the same time minimizing risk for both investors and individuals remains a challenge for widespread promotion of resilient housing. In summarizing the presentation of this research, ISET’s president Marcus Moench noted that (1) there are many known and readily available solutions for improving resilient housing, but (2) some areas, such as how to address heat and how to provide financing, require additional research and inquiry. With this understanding, there is a space for a range of actors, including local and national governments, businesses, researchers, individuals, NGOs, aid agencies, and others, to utilize these research findings to undertake many different kinds of activities to build and promote new kinds of climate resilient shelter. Learn more about ISET’s work on climate resilient shelter and more at www.i-s-e-t.org.

- BOULDER FLOODS: RECREATION, BIODIVERSITY, AND FLOODS – OPEN SPACE IN BOULDER (PART 2)

In September 2013 the Boulder area saw almost a year’s worth of rain fall in 5 days. Creeks raged, streets were flooded, houses were washed away or damaged. Four lives were lost in the county. Yet it could have been so much worse. Smart spatial planning over many years kept buildings and people out of many floodplains, so raging creeks were able to flow over undeveloped areas at a far reduced cost to property and lives. The City of Boulder alone has 42,000 acres (17,500 hectares) of Open Space – land that is set aside by the City, where no building takes place. The Open Space program has three goals: Provide opportunities for outdoor recreation Conserve local biodiversity Provide outlets for flood mitigation. The first two of these goals are met every day. But for many the value of the third goal was not evident until they saw the water washing over open fields rather than residential neighborhoods. There was still considerable damage: fences, gates, trails and other structures in Open Space were destroyed all over the city, and the cost to repair them will be in the millions of dollars. However, this cost is far lower than it would have been had these areas been developed with houses and businesses. These three goals are often in conflict: recreational users bump up against the need to close areas during raptor breeding seasons; restrictions on dogs often frustrate others who want their animals to romp free in the outdoors. Yet, the three distinct services provided by Open Space create a wider constituency of support – Boulder voters have been taxing themselves to buy and maintain Open Space since 1967. The Open Space role in flood mitigation is clearly evident in the aerial photo below. South Boulder Creek flows through Open Space along the Bobolink Trail, a popular spot with runners, dog walkers, bird watchers, and cyclists. During the deluge, the creek overflowed its banks and spread across the land on both sides. Because there were no buildings in the area, the water flowed freely with minimal damage to property and people. But when the water reached the edge of the Open Space property at the top of the photo, houses in that neighborhood were badly damaged. The water continued to flow, but now it flowed through living rooms and not over pasture. Some houses in the area had been built on raised grades, and these fared well in the flood. But many others became part of the river. Above: Aerial photo showing where flood waters overflowed into Open Space and then a residential neighborhood. Photo credit: Chris Allan (ISET-International) Above: South Boulder Creek spilling over into Open Space on the Bobolink Trail. Photo credit: Chris Allan (ISET-International) Even though this neighborhood at the end of the Open Space was hit by the flood, the damage could have been even worse. Pre-planning by the City and County reduced the some of the damage there. Some of the flooded houses in this area were built in the 1950s, and until 2010 most were not connected to the City water or sewage lines. At that time, local government officials worried that a neighborhood with septic tanks and well water in a major floodplain was a risk to public health. So in 2010, the County and City pushed residents to annex their neighborhood into the City in order to hook them up to City water and sewage. When the neighborhood flooded in 2013, the houses were damaged, but there was no contamination from water or sewage. Threats to public health were avoided. However, the neighborhood just downstream — which had declined to annex itself to the city in the past — did experience contamination in its well water for months after the flood. Boulder City Planner Chris Meschuk was quoted in the local newspaper about annexing this second neighborhood: “The interest is a lot higher.…When we met with the Old Tale Road residents, some of the people who invited us had not previously been interested in annexation, but because of the flood, their perspective had changed.” The vast majority of the time City of Boulder residents benefit from the recreation and conservation opportunities that Open Space provides. And, for those rare occasions when floods threaten the city, Open Space also provides a critical safety valve for raging creeks.

- DEALING WITH UNCERTAINTY: BUILDING URBAN WATER RESILIENCE IN UDON THANI

Blog by Richard Friend (ISET-International) and Pakamas Thinphanga (Thailand Environment Institute) Udon Thani, in the North East of Thailand, has many water needs, but management and planning processes are not yet able to account for the complexity of such a rapidly growing city. This becomes all the more problematic as the city faces some of the emerging risks that arise from climate change. As the city has expanded, demand for water has increased, while precipitation has become more variable and less predictable. The city is now facing problems with water availability and quality. The city is dependent on one main water source – the Huay Luang reservoir – that was built over 40 years ago and designed to meet the largely rural irrigation needs of small-scale rice farmers. The pressures on the Huay Luang have intensified, with the expansion of irrigated rice and other crops across the province, and increasing need to meet domestic water demands of the growing urban population. The reservoir has a capacity of 135 million cubic meters, but agriculture requires 138 cubic metres per year, and the combined demand from urban areas and industry is already at 22 million cubic metres per year. This demand is only set to rise again, as urban populations increase further, and as industry becomes more established in the area. Above: The flow of the Huay Nong Dae stream is now seriously undermined by the expansion of major roads, housing and commercial estates, undermining the natural drainage of the floodplain areas into which the city of Udon Thani is expanding. Once a viable source of water the stream is now heavily polluted. While demand has increased water availability has become more variable. Recent conditions appear to be consistent with climate projections that suggest dry seasons will become longer and drier, with precipitation in the rainy season becoming less predictable, and with more intense rainfall often in a shorter space of time. These shifts in precipitation also raise the risk of flooding – further compounded by the expansion of built-up areas across natural floodplains, altering the hydrology. During the time in which M-BRACE partners conducted a series of Vulnerability Assessments, Udon Thani experienced a widely reported water crisis in the dry season. The levels in the reservoir dropped so low, that the Royal Irrigation Department (RID) was obliged to pump the water out of the reservoir to the outflow canals. Fortunately domestic water supply to the city could be maintained but at a cost borne by farmers requiring irrigation. After such an intense dry season, RID reservoir managers were keen to ensure that they were able to store enough water in the rainy season to meet the demand of the following dry season. However precipitation patterns are also proving less reliable than historical trends, making it all the more difficult for reservoir managers to plan when to store and release water. In 2012, reservoir managers released water several times during the rainy season to avoid repeating the 2011 flood crisis. By the end of 2012 as they moved into the dry season Udon was facing a severe water shortage. In 2013 reservoir managers had already reached 70% of storage capacity only for a tropical storm and the threat of intense rainfall to move towards Udon later in the rainy season. This led the central department in Bangkok to order pre-emptive release from the reservoir to avoid the risk of flooding downstream of the reservoir and in the city. However the storm passed without any rainfall, leaving the reservoir now well below capacity. It was again a matter of luck that a subsequent, but unexpected storm did actually pass through Udon with enough rainfall to refill the reservoir. Even so, in 2014 there remains the likelihood of water shortages through the dry season, as even at full capacity the reservoir struggles to meet rising demand. Under the M-BRACE program in Udon Thani, local partners are assessing options for managing local water sources. The expansion of the urban area is leading to encroachment and degradation of local water bodies that have traditionally been sources for domestic water supply. With support from M-BRACE, the Municipality of Udon Thani, the local Rajabhat University and the Thai Research Fund (TRF), along with local people across 18 villages are conducting research to assess and map local water systems – including the flow, areas of flood risk – identifying the water bodies and wetlands that contribute to urban flood drainage and provide domestic water sources. Traditionally these water bodies provided domestic water (and some irrigation) to local rural communities. However, these have often been poorly maintained leading to declines in water quality. At the same time, as the city area has expanded, these formerly rural communities are more directly linked to the urban areas. Many of these small water bodies are being targeted as sites for development of housing estates, often with waste-water discharged from the estates directly into these waterways without adequate treatment. The combination of these pressures has reduced the water quality. With poor and unreliable water quality, the demand for water from these sources declines, pushing demand towards the piped sources from the Huay Luang. Above: Local villagers, including this village headman present hand drawn maps that identify natural water bodies, drainage and flood risk zones – and the communities that utilize these resources. In addition to the participatory maps, the researchers are using Google Earth and other sources for their research. The research is considering how rehabilitating and maintaining these bodies might improve natural drainage for the whole expanding urban areas, as well as provide additional water sources in a more decentralized, modular water supply, thus contributing to the flexibility, diversity and redundancy of the urban water systems. This kind of research, in which local people in partnership with government agencies and research centres take the lead in assessing and mapping a water sources, is important for the information that it generates. Additionally, such a collaborative research process that involves both citizen and expert-led science contributes to opening arenas for broader informed public policy dialogue. These processes lie at the heart of building resilience – creating new arenas for state and citizens to enter into informed public dialogues for both assessing vulnerability as well as identifying innovative options for action. Acknowledgements: Mekong-Building Climate Resilience in Asian Cities (M-BRACE) is a four-year program funded by USAID that aims to strengthen capacity of stakeholders in medium-sized cities in the Thailand and Vietnam region deal with the challenges of urbanization and climate change. The program is implemented by ISET-International, in partnership with the Thailand Environment Institute (TEI) and NISTPASS. This blog article draws on original research being conducted under the M-BRACE program led by Dr. Santipab Siriwattanapiboon (Rajabhat University, Udon Thani) and Ms. Pattcharin Chairob (Thai Research Fund), as well as the M-BRACE Vulnerability Assessments.

- EXPERIENCES, VIEWS AND PRACTICAL IDEAS FLOW AT THE ANNUAL UCR-COP PLANNING MEETING

By: Stephanie Lyons and Thanh Ngo, ISET-Vietnam It was excellent to see more than 50 UCR-CoP participants get together at our annual planning meeting last week to catch up, discuss their work in urban climate resilience, and map out collaborative efforts for 2014. Last Tuesday, February 18, nearly 60 people from around 30 different organizations (representing the majority of the UCR-CoP’s approximately 40 member organizations) met at the offices of the Association of Cities of Vietnam (ACVN) in Cau Giay, Hanoi to plan the UCR-CoP’s direction in 2014. Everyone had a chance to meet someone they didn’t already know and share the details of their upcoming work in the field of urban climate resilience (UCR) in 2014. Participants then got together to exchange information and ideas for UCR activities in 2014 – from training and capacity building efforts to policy work, good practice documents, seminars, lessons learned processes, workshops and field trips. A lengthy list of confirmed, planned and proposed activities was compiled under four categories: Mainstreaming UCR into policy and decision-making Sharing knowledge and lessons learned, including through online engagement Research methodologies and impact Capacity building and training Under the above categories, participants separated into working groups to brainstorm and identify opportunities to work together on shared activities in 2014. After reflecting briefly on the most successful and useful activities in 2013 (and why), each group came up with a list of practical steps for taking work forward this year. As a focal point for members to share details of upcoming activities, the shared calendar that can be found in the right column of Urban climate resilience – Community of Practice (UCR-COP) blog is the effective tool to connect members and related stakeholders. The Urban Development Agency (Ministry of Construction) also provided a highly instructive overview of the recent Decision 2623 (Approval of Scheme ‘Urban Development of Vietnam Responding to Climate Change in the Period 2013-2020’). The meeting minutes as well as all presentations and other content from the meeting will be shared with all UCR-CoP participants this week. As a co-facilitator of the UCR-CoP, ISET again thanks all those who attended for their enthusiastic contributions. We look forward to continuing to work with you and watching as you take both individual and collaborative efforts forward as participants of the UCR-CoP in 2014. Original posted by http://www.urbanclimatevn.com

- BOULDER FLOODS: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE (PART 1)

Between September 11 and 15, 2013, Boulder received over 15 inches of rainfall (Daily Camera, 2013 Floods) resulting in severe flooding that destroyed 345 and damaged 557 houses, damaged 150 miles of county roads, and killed 4 people. Experts have claimed that this particular event was a 1000-year rain and a 100-year flood. The reality, however, is that floods are not new to Boulder (Static BoulderColorado). Floods have been recorded in Boulder and the surrounding areas since 1844. Between 1844 and 1900, 10 floods were reported, of which 3 occurred in 1864 alone. Despite the frequency of floods, flood mitigation only entered public consciousness after the 1894 floods, during which peak discharge was estimated between 7,400 and 13,200 cubic feet per second and floodwaters destroyed building, roads, and bridges. Mitigation measures taken at this time included raising the ground up to 3 feet in certain areas and rebuilding the railroad on higher ground. The next 60 years, however, were marred by a lack of action. The Boulder City Council appointed dozens of consultants to suggest flood mitigations, but most of the reports were shelved due to a supposed lack of funds. Despite this, Boulder still did not take action when federal funds were made available through the Flood Control Act. The main issue at hand was a lack of public interest in flood mitigation. After all, floods had not occurred between 1939 and 1964, likely causing people to forget the effects of floods and/or become complacent. Many also had a false sense of security that the Barker Dam, constructed in 1910, would protect them from future floods. In addition, many felt that the risk of building in a floodplain was theirs to take without interference from the City. Public interest in flood mitigation was ignited in 1965, after floods in nearby Denver resulted in the loss of 2,500 homes and 750 businesses, and again in 1969 after a 25-year flood in Boulder. Yet, although flood awareness had increased, people were unwilling to support changes in zoning and building codes and stricter floodplain regulation. Therefore, the Council implemented less ‘invasive’ measures such as requiring buildings in certain areas to be flood-proofed and disseminating drainage information. In the late sixties and early seventies, national conversation on flood mitigation changed with the establishment of the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Communities participating in the NFIP were eligible for federally backed flood insurance provided that they incorporated flood mitigation into planning and development. It was with this shift in the national mood and major floods in South Dakota in 1972 and Big Thompson in 1975 that the Boulder Council began to take significant action. They defined the floodway, revised floodplain regulations and permits, assessed flood risk of tributaries, produced detailed flood plain maps, and joined the NFIP. In terms of mitigation, the public was and continues to be against structural solutions such as concrete floods walls and lining the creeks. Consequently, since the 1970s the Council has largely focused on non-structural solutions such as early warning systems, stricter building codes, and multi-purpose structural solutions such as creek-side bike paths. In light of the recent, severe flooding, what will happen? How will discussions concerning flood mitigation change and/or progress? What must be remembered, as discussions continue, are the following lessons learned from the history of flood control in Boulder: Flood mitigation was only taken seriously after major flooding events and with a change in the national conversation about flood mitigation. When floods don’t occur for long periods of time, people forget/become complacent. Public support for flood mitigation initiatives tends to focus on soft solutions such as open space, greenways and multi-use paths that double as floodways. Seen through this lens, the September 2013 floods provide a window of opportunity that many players in the City and County of Boulder are considering how to best leverage to build resilience.

- Sharpening Our Focus on Urban Disaster Risk Reduction

By Stephanie Lyons and Tho Nguyen, ISET-Vietnam Efforts in disaster risk reduction (DRR) in Vietnam to date have primarily focused on rural areas and often employ effective community based disaster risk management (CBDRM) methods, yet there is an intensifying need for better DRR approaches in urban contexts. In a country experiencing rapid development, many communities in urban and peri-urban areas are increasingly vulnerable to natural hazards and disasters. Policymakers, practitioners and researchers met in Da Nang in April at a workshop organized by the Disaster Management Center (DMC) and the Institute for Social and Environmental Transition (ISET) Vietnam to share their knowledge and experiences in both urban and rural DRR. At this event, 14 cities from across Vietnam came together with government agencies, NGOs and researchers to exchange experiences and identify current challenges and potential solutions for improving urban DRR in Vietnam. Key points raised during the workshop Current disaster management policies and efforts focus largely on emergency response and disaster recovery, and less so on risk reduction, prevention and adaptation. Major natural hazards and disasters around the world over the past decade – including Hurricane Katrina in 2005, typhoons in 2009, and the 2010 Haiti earthquake – highlighted that governments can be immobilized by disasters, and recognition of this has helped shift perspectives towards the need for greater expertise in urban DRR. Existing laws, guidelines and interventions relevant to DRR – such as the National Green Growth Strategy and Construction Law – are not sufficiently coordinated or synchronized, do not fully address or facilitate DRR in urban areas, and do not provide comprehensive or effective mechanisms for multi-stakeholder and cross-sector coordination and information sharing. Policymakers must carefully consider the appropriate levels of delegation for decision-making, from the local to the provincial and national levels. In particular, local authorities should be able to access and apply up-to-date information and data to inform their DRR planning. While the established approaches often used in the field (such as CBDRM) are highly instructive, urban contexts demand tailored approaches to community engagement, and local knowledge must play a central role in building resilience over the long term. Many communities throughout Vietnam are already accustomed to dealing with natural disasters, and this resilience should be recognized as a strength. However, it is crucial to actively engage community members in DRR decision-making and education about risks, prevention, and response mechanisms. Urban DRR implicates a wide range of stakeholders, including governments at all levels, international donors, civil society, academia, business, and local communities. Concerted private sector engagement in DRR planning and implementation is still limited, despite the significant potential for businesses to play a more central role in supporting more effective urban DRR. There is a need to clarify the incentives for deeper business engagement and explore the potential for public-private partnerships. A new Natural Disaster Prevention Law, effective from 1 May 2014, is expected to initially address these issues by providing a systematic legal framework to regulate DRR-related actors and actions in rural and urban areas. Keep an eye on the UCR-CoP blog in the coming months for a forthcoming publication on the challenges and solutions for urban DRR in Vietnam, which will build on the experiences, lessons and suggestions discussed at this workshop. Original post by UCR-CoP blog

- LEARNING FROM COMMUNITY-BASED MANAGEMENT MODELS UNDER THE NORTH VAM NAO WATER CONTROL PROJECT

Published March 3, 2014 On January 11, 2014, the Climate Change Coordination Office (CCCO) in Can Tho traveled to An Giang to learn about the experiences from the community-based management model used under the North Vam Nao Water Control Project II (NVNWCP-II). The project was funded partially by AusAID and Vietnamese State for implementation in Phu Tan and Tan Chau provinces from 2002 to 2007. The water control system has been in operation since 2008 and has already shown positive results. The project’s goal was to help An Giang province establish and operate a socially and environmentally sustainable water management system in North Vam Nao which would benefit the local economy by helping to alleviate poverty. Through a coordinated approach to water and land management, the project aimed to demonstrate both economic and social benefits to the Vam Nao community, particularly in the areas of environmental improvement and poverty alleviation. Although the design and building techniques used under the NVNWCP-II cannot be directly adapted to the smaller-scale Can Tho project called the “Community-Based Urban Flood and Erosion Management for Can Tho City” funded by the Rockefeller Foundation from 2013 to 2015, the CCCO found the NVNWCP-II’s community-based management model to be a good model to learn from. Participatory management was a defining element of the NVNWCP-II. The community participated in the project from the beginning and throughout the life of the project. During the survey process for structural design, people’s opinions about their needs and expectations for solving local problems were carefully considered (for example, in relation to water management and environmental pollution issues). The community also helped supervise the construction process during the building phase, and contributed to the building process for the ring-dyke, boundary canals and sluices of project areas. During the implementation phase, project areas were divided based on irrigation areas instead of administrative boundaries. There were 24 sub-areas under the project, with each compartment covering around 1000 hectares. Each compartment management board was voted in by the local people under three-year terms. Locals were encouraged to consider and vote for candidates on the basis of whether they: 1) owned land in that sub-area; 2) had farming experience; 3) were hard working; and 4) had a stable income. Compartment management boards had responsibility to form and implement production planning of sub-areas, manage and secure ring-dyke, boundary canals and sluices, help solve any disagreements between households, and remain connected with the management board of NVNWCP-II. One difficulty of the model was the unofficial payment regulation for the compartment management boards. Currently, the An Giang provincial government pays around 2.5 million VND per month to the compartment management board. In the future, this allowance will be contributed by local households in the compartment sub-area. The Can Tho CCCO greatly appreciated the NVNWCP-II management board’s willingness to share its experiences, and learnt valuable lessons from the trip. “If they can manage their people at such a great scale, why can’t we?” reflected the leader of Area 5, An Binh ward at the end of the meeting. Original posted by http://urbanclimatevn.com/ Reported by the Can Tho CCCO.

- INTERVIEW WITH THE RESILIENT HOUSING DESIGN COMPETITION 2013 WINNERS (INDIA)

by: Michelle Fox, Director of Art + Communications Shifting our approach Shelter accounts for the highest amount of monetary losses in climate related disasters (Comerio, 1997). Housing is often the single largest asset owned by individuals and families. After a storm or natural disaster, resources are focused on restoring shelters to their previous state of operation—often times rebuilding with little to no modifications to the previous design—simply bouncing back. However, what we have found through our economic analysis in Vietnam and India, is that simple storm resistant construction techniques can be employed to protect shelter from avoidable damages and costs. We argue that investments into construction prior to a storm, proves more cost effective than spending on post-disaster recovery. With this finding we are encouraging households to bounce forward—learning from the mistakes of the past and considering the future uncertainty of climate change. How to build? Resilient Housing Design Competition 2013: Call for Entries In support of our study, we hosted the Resilient Housing Design Competition 2013. We called upon the knowledge of local architects and builders to submit designs that considered shelter in the context of flooding and rising temperatures. At ISET-International, we place high value on the experiences and knowledge of local residents and have been extremely pleased with the creativity and innovation of their response. Winners announced A panel of judges reviewed many impressive entries, but only one selection could be made for the professional category. We are excited to announce Kalpit Ashar and Mayuri Sisodia the winners of the India Resilient Housing Design Competition! Together this team, better known as Mad(e) in Mumbai, developed a housing design that is not only low-cost and beautifully designed, but flood and heat resistant as well! Congratulations to you both! BELOW IS OUR INTERVIEW WITH KALPIT OF MAD(E) IN MUMBAI. Please describe your background and education in architecture. How long have you been a professional architect? Our undergraduate education in architecture took place in Mumbai, which has majorly shaped the philosophy of our practice and thinking towards cities and architecture. Both of us completed our undergraduate course from Kamla Raheja Institute for Architecture, Mumbai and went to different cities to study further. Mayuri went to London with Charles Wallace Trust award and completed her Masters in Urban Design at The Bartlett, University College London and I pursued Masters in self-sufficient habitats, digital tectonics & emergent territories at Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia, Barcelona. After graduating, we worked with Charles Correa Associates and worked on various national & international projects. We have been also involved with Kamala Raheja Institute for architecture as a design faculty since 2008. Together we formed MAD(E) IN MUMBAI, to pursue our interests in art, architecture and cities. MAD(E) IN MUMBAI has won many national and international design competitions which include ‘Rethinking Kala Nagar Traffic Junction’ organised by BMW Guggenheim Lab, ‘Revitalization of Banganga Crematorium’ organised by the Rotary Club; and the International Design Competition for Sustainable Community Center organized by International Conference for Humane Habitat. What was your motivation in entering the Resilient Housing Design Competition 2013? What attracted us most towards the competition was the phenomenon of resilience itself. We saw resilience here as an ability of architecture to soak the forces of nature and transform itself with seasons and changing rhythms of water. This lens allowed us to transcend the conventional notions of architecture from solid, unchangeable entity towards dynamic process transforming with time. Another aspect of the competition that interested us was the idea of low cost dwelling. In case of flooding, the poor are the worst affected sections of society as the sprawling city pushes them towards margins and low-lying areas. The attempt of the competition to contribute towards social equity and creation of socially viable environments interested our practice. Also in terms of tectonics, low cost housing was an interesting and challenging phenomenon for us. We saw it more as an opportunity instead of a restraint. Both of us have always been inspired by simple and local techniques of construction deployed in various geographies of India. This competition gave us a platform to express and explore our interests in assembling local materials together. What type of research did you do when developing designs? Were you already familiar with low-income communities, and did you do any site visits during your research? Our research mainly included low cost housing in Indian context. We studied works of Laurie Baker and a few other architects whose practice focuses on developing architectural responses for poor households using locally available materials. Are climate resilient shelters a topic of discussion in India, or is this an emerging field? Do you find clients and communities receptive to design considerations that relate to climate change? Earlier, the climate resilient shelters were discussed on public forums when a major disaster took place. Within the last decade, the consciousness towards resilient dwellings has increased internationally and nationally in a public domain. Unfortunately, at the ground level, people are not yet aware of the phenomenon even in metropolises like Mumbai. The residential developments that sweep the city today tend to ignore the relationship of habitat with the climate, seasons and hydrological processes making them vulnerable to natural disasters in future. Have you ever considered climate change and resilience in previous designs? Resilience is an evocative idea for us and we would love to explore the idea in all possible directions through variety of projects and contexts. You have included many details to reduce the threat of flooding and heat in the RHDC 2013 winning design. What concepts are you most proud of, and why? The project revolves around four simple ideas that fundamentally shape the dwellings. They include: Building city scale resilience Here we discuss strategies of contributing towards city scaled resilience. Each residential plot is designed to develop 20% of its land as a water body that could soak flood water. These water bodies multiply across the landscape as rainwater harvesting systems where water is collected, purified, circulated and celebrated. The houses grow around the water body. Aqueous house typology Here we question stilted typology of flood resilient housing and develop a house rooted in its people’s relationship with the ground plane. Thus, the house gradually lifts up to relate to the ground and lets the water flow beneath towards the tank. Neighborhood Here we question the monotonously repeating landscapes of flood responsive houses and design strategies towards formation of an intimately stitched neighborhood. Local techniques of construction Here we deploy simple construction techniques of assembling bricks, bamboo and terracotta together used by local craftsman and masons. How have you personally seen shelter and climate affect your community? We could recall the floods of 26th July 2005 in Mumbai that caused considerable damage to the city and the neighborhoods. The unplanned residential developments that interfere with the natural paths water take to reach the sea were one of the prime causes of the floods. If the habitats of the city respect the hydrological processes of the topography and allow the water to make its way, then these devastating incidences could be avoided. Here we highlight the resilient systems of this winning design entry. Download the 4-page pdf here ____________________________________________________ Reference: Comerio, M. C. (1997). Housing issues after disasters. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 5(3), 166–178. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.00052 The Resilient Housing Design Competition 2013 was hosted by ISET-International, Gorakhpur Environmental Action Group, and Seeds India as part of the Sheltering From A Gathering Storm project.

- ALTERNATIVE DEVELOPMENT PATHWAYS: EXAMINING THE DA NANG MASTER PLAN

By Thanh Ngo and Stephanie Lyons; ISET-International, Vietnam What will happen if a city’s master plan doesn’t address flood risks in the context of climate change? This crucial question is addressed in a Da Nang Policy brief released earlier this year by ISET-International under a project funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. The policy brief, entitled “Alternative development pathways: Examining the Da Nang master plan”, explores the implications of Da Nang’s current city master plan and its focus on new and planned growth in the low-lying floodplain, and how urbanization processes have changed the nature of flooding hazards for the city. The brief notes that the plan is likely to lead to negative consequences for poor communities in low-lying areas adjacent to the new development. Da Nang will experience an increase in flood frequency and severity due to land use, the orientation of roads, and other infrastructure that interact with heavy rainfall by blocking drainage or diverting water to locations that were previously not at risk. Based on the calculation of ARUP experts, the capacity of the Vu Gia and Thu Bon river system is 20 times lower than the capacity required to reduce the impact of potential flood events. Extreme rainfall will also increase, as climate change is likely to increase the intensity of moderate to severe rain events in and around Da Nang. Conventional urban planning, infrastructure design and foundation standards based on historical experience will not prepare houses and infrastructure for future events and lead to more flood damage to the whole regionUrban planning decisions, based on historical experience, that increased the elevation of land for construction resulted in more flood damage to the whole region. However, implementation of plans implementation of urban development plans in Da Nang isis still proceeding without significant modification, despite the known risks. If no action is taken, there will may be more greater economic damage and possible loss of life. This policy brief offers informative yet valuable messages to policy makers, local governments, and relevant stakeholders on sustainable resilient development. To reduce the impacts of climate change in Da Nang, proven resilience approaches that can help protect the future urban development of Da Nang city should be found.

- THE ECONOMICS OF STORM RESISTANT SHELTERS

Michelle Fox, Director of Art + Communications, ISET-International Phong Tran, Ph.D, Technical Lead, ISET-International, Vietnam In October 2011, The Women’s Union (WU) of Da Nang Vietnam, working with the Institute for Social and Environmental Transition (ISET), proposed a microcredit and technical assistance program aimed at developing storm resistant shelters in vulnerable districts of Da Nang called The Storm and Flood-Resistant Credit and Housing Scheme in Da Nang City (The Project). Due to the many coastal and flood prone neighborhoods throughout the city and a growing population of 926,000, intense storms and frequent flooding have become a harsh reality for Da Nang’s citizens. With limited resources and relief efforts being prioritized over disaster risk reduction, the residents of Vietnam have been offered little opportunity to seek shelter from the next storm, often rebuilding after a storm with the same flawed construction technique as before. With funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, ISET, WU, Da Nang Climate Change Coordination Office (Da Nang CCCO), and Central Vietnam Architecture Consultancy (CVAC) banded together to fill the critical gap between one disaster and the next—developing a mechanism which both rebuilds and protects. Two years later, on October 15, 2013 Typhoon Nari (typhoon no. 11) landed in Da Nang city at dawn with level-12 winds and level-13 gusts equivalent to 130km/h. Persistent storm winds coupled with heavy rainfall led to flooding in many areas of the city. The typhoon caused severe damages—many people were injured, thousands of homes endured damage to the structure and roofs, and tens of thousands of trees either broke at their trunk or were uprooted by the severe winds and clogged critical roadways. According to the report of Da Nang City People’s Committee, an estimated total damage is up to 868.8 billion VND (~$41M USD). The Project is Proven Resilient By the time Typhoon Nari made landfall, 244 of the 245 beneficiary households had completed construction thanks to The Project, and all 244 households were safe from Typhoon Nari’s force. In the time leading up to the storm, beneficiary households strengthened their houses and carefully prepared to cope with the typhoon season. While beneficiary houses stood strong, structures all around them suffered heavy damages. This tragic event demonstrated that investment into preparation is much more effective than spending on post-disaster recovery, in addition to the peace of mind the safety brings to the community. Our hope now is that this experience will inspire other groups and households to employ the same storm-resistant building techniques that were installed in each of the beneficiary households. More information in Lessons From Typhoon Nari | Bài học từ cơn bão Nari:(available in both English and Vietnamese): English : Vietnamese Above: Just days after the typhoon, ISET and the Women’s Union toured beneficiary households, and were pleased to find the structures dry and intact! Above: While in Da Nang, ISET and the Women’s Union also toured households who were less fortunate and in need of reconstruction due to the typhoon’s force. Room for Improvement Storm resistant shelter designs are one of the fundamental requirements of climate resilience at the household and community level along with access to loans to allow households to apply typhoon resistant construction techniques when retrofitting and building their houses. Important stakeholders such as professional agencies/experts still rarely participate in the construction of local low-income housing in peri-urban and hazard prone areas. Some obstacles, such as high costs of design services for low-income households and limited access to loans for housing, require local governments to initiate appropriate supportive policies or subsidy programs to reduce obstacles and to bridge this gap. Other needs of improvements lie within the limited self-sufficiency of households living in hazard prone areas, which is linked to their limited financial resources. Local governments, together with the public and private sector, need to plan and implement actions for local economic development (e.g. programs for vocational training or micro-finance opportunities). Next Steps To support the Women’s Union and other organizations promoting storm resistant housing, ISET-International with funding from the Climate Development Knowledge Network (CDKN) undertook a 2-year long cost-benefit analysis research project to estimate the average economic costs averted from building to storm resistant standards in Vietnam as well as India and Pakistan. This study also supported the Resilient Housing Design Competition 2013, which called for innovative storm resistant shelters for low-income households. Plans for scaling and replication of the project model are currently being investigated. Final outputs from this project will be available at i-s-e-t.org/Shelter in mid-March 2014. The winning team of the Vietnam Resilient Housing Design Competition was TT-Arch, a firm based out of Hue, Vietnam. The team, along with other finalists, toured the beneficiary households of The Project in Spring of 2013, and included some of the same storm-resistant building techniques that were installed at those sites. Below is a detailed description of their winning design and the key characteristics that ISET is now recommending to households.

- VULNERABILITY AND RESILIENCE: BOULDER FLOODS OF 2013

By Chris Allan and Karen MacClune “By 6 AM on Thursday morning, there was a huge river of water flowing through main street, where the two rivers in town had become one about a quarter mile wide,” said one Lyons resident. “By mid-morning Thursday a footbridge in town was gone, and cars were washed down river. The town was cut off into six islands, and no one could move between them.” Gas, electricity, and water were all cut off, and only the National Guard could get in and out of town in their amphibious vehicles. “The Town staff organized the evacuation center. Victoria, our Town Administrator, was fantastic. The Town board did a lot, and the fire department did a lot. The Town just took care of itself.” “Store owners and restaurants just opened up. People cooked on camp stoves, propane grills. On Thursday and Friday the town did big street parties. Every island did the same. People were eating all the perishables before they went bad. I volunteered at the evacuation center on my island, just doing what needed to be done.” “Everyone in town knew each other, at least in passing. It’s a small town. Some people from the mountains had to hike down, they would show up at the evacuation center after 12 hours of hiking. People would see someone they knew and had been thinking about, and would burst into tears. But people for the most part were in remarkably good shape.” “By Saturday, the water was down enough to drive out. High clearance vehicles could get out in morning, anyone by the afternoon. Getting out was weird. We had been so cut off, it was very strange to come out and go to grocery store in Longmont. There was power, people were living their daily lives…In Lyons, it was a disaster zone, it was all about helping people in need. It was hard to leave that.” “When we evacuated we arrived at a church shelter. We pulled up, and guys came out with umbrellas and said “welcome”. It was sweet. But it was also the first time I felt like a victim, it didn’t feel good. We had been sent there to register with FEMA, as soon as we realized FEMA wasn’t there we turned around and went elsewhere.” “If we’d had to stay, it would have been awful. It was so disempowering.” Video Credit: Jem Moore

- LESSONS LEARNED FROM TYPHOON NARI (KÈM BẢN DỊCH TIẾNG VIỆT)

41 million USD-that’s the estimated total damage of Da Nang City, Vietnam after Typhoon Nari swept through Vietnam in the morning of October 15, 2013. Right after the typhoon, ISET-Vietnam and Da Nang Women’s Union conducted an assessment of damages and resilience capacity of beneficial wards in the storm-resistant housing project. Although quite modest in scale, the success of this project is highly appreciated by local government and community, especially after Typhoon Nari. This report shows the immediate success of intervention efforts that were provided to 244 households in Da Nang City with the goal of developing storm resistant shelters. 100% of the houses were proven resilient during Typhoon Nari, which hit Da Nang on October 15, 2013. This report is available in English and Vietnamese, to download PDF file please visit: http://i-s-e-t.org/resources/working-papers/lessons-typhoon-nari.html Report Authors: Dr. Tran Van Giai Phong, Technical Lead, ISET-Vietnam Bài học từ cơn bão nari 41 triệu Đô La Mỹ là con số ước tính thiệt hại của Đà Nẵng do cơn bão Nari đổ bộ vào Việt Nam sáng ngày 15 tháng 10, 2013 Ngay sau khi bão tan, ISET-Việt Nam và Hội Liên hiệp Phụ nữ thành phố Đà Nẵng đã tiến hành đánh giá tình hình thiệt hại và khả năng chống chịu của các phường xã hưởng thụ dự án nhà ở phòng chống bão. Mặc dù quy mô của dự án khá khiêm tốn, nhưng tác động của dự án được cộng đồng và chính quyền địa phương đánh giá cao, đặc biệt sau trận bão Nari. Báo cáo này chỉ ra thành công bước đầu của các nỗ lực can thiệp, hỗ trợ đối với 244 hộ dân ở thành phố Đà Nẵng nhằm mục tiêu xây dựng nơi trú ẩn an toàn với bão lũ. 100% các hộ đều chứng tỏ được khả năng thích ứng của mình khi trải qua cơn bão Nari, đổ bộ vào Đà Nẵng ngày 15/10/2013. Để tải báo cáo bằng Tiếng Anh và Tiếng Việt xin truy cập: http://i-s-e-t.org/resources/working-papers/lessons-typhoon-nari.html Tác giả: TS. Trần Văn Giải Phóng, Phụ Trách kỹ thuật, ISET-Việt Nam